“Use hospitality one to another without grudging.” — 1 Peter 4.9

Hospitality is the forgotten qualification of Christianity. It is probably the most overlooked requirement of elders. It is a requirement for widows who will be supported by the church. I don’t think I have ever been in an ordination meeting where the candidate was examined on the basis of his track record of hospitality, and yet, there it is. Sixth on the list, right before the never overlooked “apt to teach”.

Not only is hospitality a requirement for church ministers, it is one of the few admonitions that Peter connects to how Christians should behave given that “the end of all things is at hand.” Watchful prayer, fervent charity, body ministry… and sincere hospitality. These are probably not the attitudes or actions that one would intuit when contemplating the end times, especially not hospitality. “The end of the world is upon us, quick, invite some people over for dinner!”

Hospitality is so much more than just inviting friends over for dinner, or lodging a missionary in your home for a week; although some would do well to start there. The word that is translated as hospitality is “philoxenia”. Like many such words, this one has its meaning etched directly on the surface. “Philo” is love and “xenia” is stranger. So, love for strangers. It is mostly the opposite of “Xenophobia”, meaning fear or rejection of strangers. And by strangers, it is referring to those not like you. Not your household, not your family, not your friends, not your church brethren. You can confirm this by considering that this same word (philoxenia) is translated in Hebrews 13.2 as “Be not forgetful to ‘entertain strangers’ [philoxenia]“–which, in my inconsequential opinion, is a masterful translation.

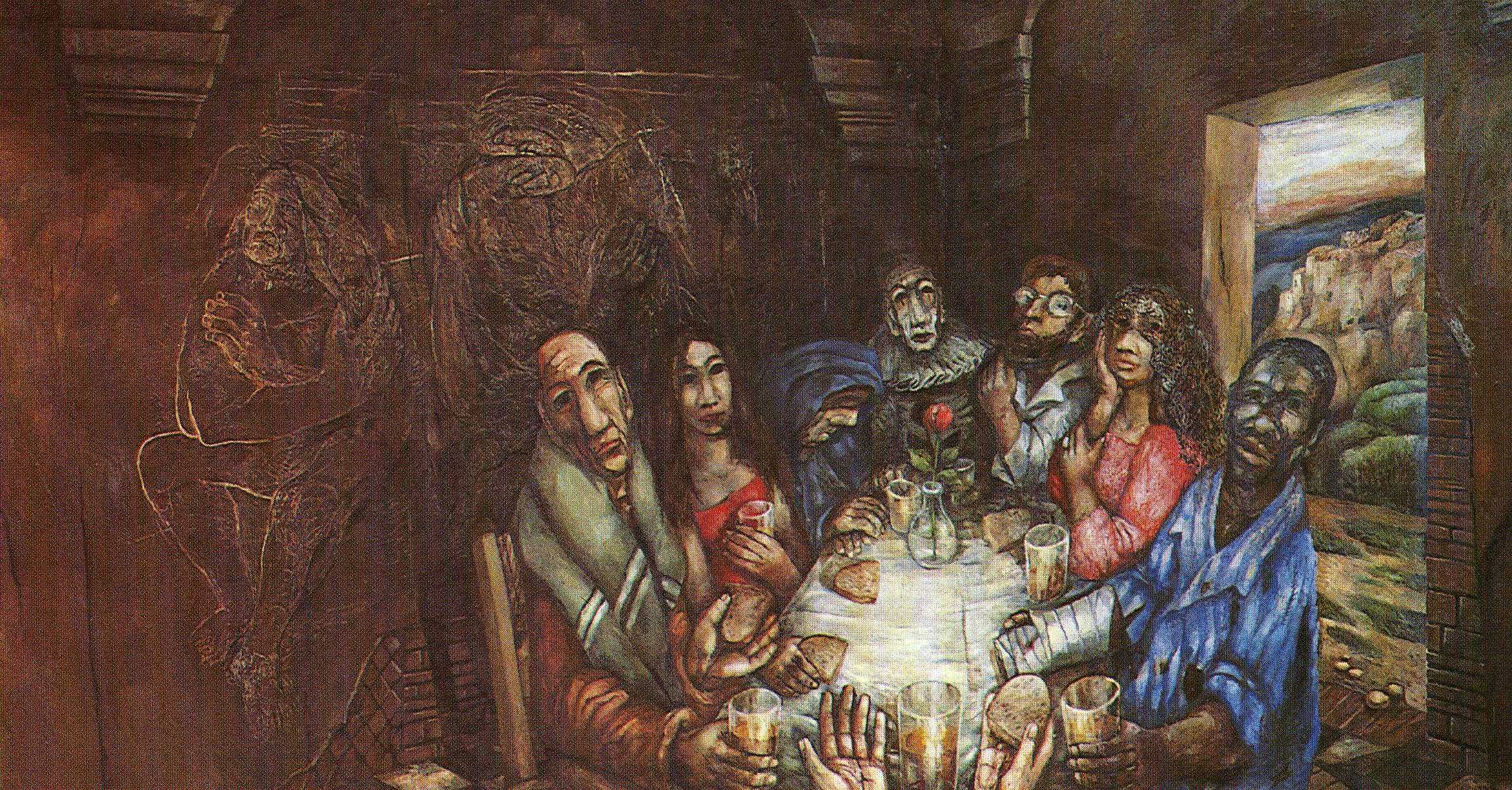

True hospitality is the fulfillment of the teaching of Jesus in Luke 14 where he instructs us not to call our friends, our brethren, our kinsmen, nor our rich neighbors, but rather the poor, maimed, lame, and blind. This kind treatment of those that are not our community is the spirit of hospitality. One way to think about it is that “Love Thy Stranger” is the true meaning of “Love Thy Neighbor”, as Jesus famously illustrated in the parable of the Good Samaritan.

This hospitality is far more meaningful and substantive than simply inviting a bunch of homeless vagabonds over for meatloaf dinner. That would be a simple way of actually avoiding the admonition of “Love Thy Stranger”. Rather, real hospitality would resemble Christ’s treatment of the strangers, the unwanted, the despicable. He sat with them, ate with them, spoke with them; he saw them, he cared for them, he ministered to them. His hospitality often manifested itself when he accepted their hospitality–dining with them in their houses. Preferring their company over the company of intellectual and religious “equals”; which, of course, galled those “equals”. He did not approve of their sins, but he did not despise their persons.

It is one of a long list of striking contrasts between the Old and New Testaments, that in the New Testament the holy is mixed into the unholy. In the Old Testament, things are holy only so long as they are kept separate and isolated. The moment that something holy come into contact with something unclean, the holy is ruined. Too many Christians behave as if that were still the case, and that their sanctification was that precarious. However, under the New Testament, sanctification is not a function of geography or categorization or fraternizations. Under the New Testament the mighty Spirit of God has sanctified the believer through the same operation of power that raised Jesus from the dead–not by isolating from death or hiding from death, but by marching right up to Satan’s front door, kicking it off its hinges, stripping him of all of his weapons, and taking captive the captivity; and all of this in broad daylight, and there was nothing that anyone or anything could do about it. (Read Romans 8:31-39.) We are holy because He is Holy.

And now, unlike under the Old Testament, God has commissioned us to mingle and mix with the unholy world. Not for the purpose of becoming like them, that is not possible. (Read 1 John 3:4-10.) We are deployed into the world as salt and light–our presence sanctifies our environment. The world doesn’t rub off on us, we rub off on the world. Holiness in the New Testament is the power that sanctifies those around us, not the rules that quarantines us from them. (Read 1 Corinthians 7.12-16.)

This great commission is thwarted when we sneer in righteous indignation at those who through fear of death have all their lifetime been subject to bondage. Instead of diving in, bringing the sanctifying presence of Christ into their sad, miserable lives, we ooze a feigned holiness so impotent that the mere salutation of a sinner would terminally wound it. The Church is not weak because it has mixed with the people of this world. It is weak because it has withdrawn itself from the world, and cloistered itself in a nauseating display of “holiness signaling” that is really a mechanism to mask our fear of them, when in reality it is the world–or the world’s spiritual powers of darkness–who should fear us. (Read 1 John 2.13-14 and 2 Corinthians 10.3-6.)

Seeing, then, that the end of all things is at hand, what manner of persons ought we to be in all holy conversation and godliness? We should be, among other things, hospitable. We should Love our Strangers.

M. N. Jackson is a founding elder and teaching pastor of Free Born Church. He was a missionary in Mexico for over 20 years where he was part of a team of church planters. After being deported from Mexico for preaching the gospel, he returned to San Antonio, and continued ministering the word.